D-day 4: I am Korean-American

Chapter 1 The First Wave of Korea Immigration

Chapter 2 Korean Picture Brides and the Korean Independence Movement in America

Chapter 3 The Korean War and the Second Wave of Korean Immigration

Chapter 4 The Immigration Act of 1965 and a New Group of Korean Americans

Chapter 5 Striving for the American Dream and Korean Small Businesses

Chapter 6 Korean Churches in the United States

Chapter 7 Los Angeles Koreatown: Past and Present

Chapter 8 Korean Americans and Education

Chapter 9 Korean American Ethnic Identity

Chapter 10 Los Angeles Riots 1992 and the Remaking of Korean American Ethnic Identity

**Rightful

credit goes to:**

© Korean American

History

Hyeyoung

Kwon (University of Southern California)

Chanhaeng

Lee (State University of New York at Stony Brook)

Korean Education Center in Los

Angeles 2009

Chapter 7 Los Angeles Koreatown: Past and Present

Background:

Currently located in the Wilshire district, Los Angeles Koreatown got its official name “Koreatown” from the City of Los Angeles in 1980 as a result of the noticeable increase in

Korean population and Korean-owned business throughout the area. Before the 1950s, as Angie Y. Chung pointed out, the Wilshire district served as a commercial and residential area for White Angelenos. With the elimination of residential segregation statutes in 1948, however, African Americans began to move into the district from South Central Los Angeles.

Many newly-arrived Korean immigrants also moved into the district and opened businesses. The first mini-mall was built at 3122 West Olympic Boulevard in 1971 when Hi Duk Lee, a former miner in West Germany, opened the Olympic Market in the same building and rented out the remaining units to other tenants. Since 1971, Koreatown has undergone many transformations. Olympic Boulevard became the heart of Korean business activities, displaying Korean language signs. Later on, Koreatown expanded to include Western and Vermont Avenues and other major streets west of the downtown.

Koreatown in the past

Bong-Youn Choy estimated that about 1,000 Korean plantation workers moved out of Hawaii to the mainland for better economic opportunities between 1905 and 1907. In Los Angeles, Korean Americans rented a house in the Bunker Hill area to establish the first Korean Presbyterian Church in 1906. In the 1910s, around 40 to 50 Koreans lived on Macy and Alameda Streets and the Bunker Hill area. The residential area of Korean Americans shifted to an area surrounded by Vermont, Western, Adams, and Slauson Avenues in the 1930s during which the Korean Presbyterian Church built its own church at 1374 West Jefferson Boulevard.

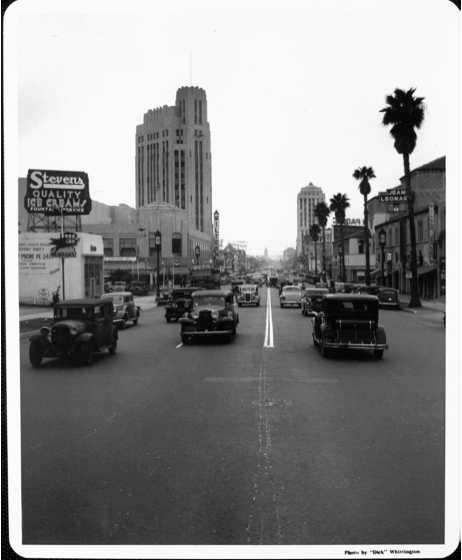

The Wiltern Theatre on the corner of Wilshire Boulevard and Western Avenue in Los Angeles, cir. 1938 (Photo from the Special Collections of University of Southern California)

Korean Presbyterian Church in Los Angeles, cir. 1930 (Photo from the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection)

After the immigration reform of 1965, Koreatown became the major destination point for incoming Korean immigrants to the United States. Koreatown grew rapidly and started to develop many social service agencies and media stations to assist newly-arrived immigrants. The place offered cultural comforts to many immigrants who faced language barriers. Over time, Korean immigrants used their entrepreneurial skills and resources to turn Koreatown into an economically booming community. In 1982, with the help of the Koreatown Development Association (KDA), California Department of Transportation officially put a “Koreatown” sign on Freeway 10 between Normandie and Western entrances.

Koreatown today

Koreatown is still home for many newly-arrived Korean immigrants. In contrast to its name, however, Koreatown is a multiracial neighborhood. The vast majority of residents in this neighborhood are Latinos. A report of the 1990 U.S. Census found that Korean Americans made up less than 15 percent of the residents of Koreatown.

The Wiltern Theatre on the Earth Day, April 22, 2008 (Photograph by Chanhaeng Lee)

While Koreatown still serves as the heart of different Korean American community organizations, television, radio, and news media, as well as various religious organizations, the main characteristic of an ethnic enclave—a socially and spatially constrained place occupied by newcomers whose low-income status and racial segregation forced them to develop a place of their own— is gradually disappearing. Once housing discrimination was abolished, many wealthy Korean immigrants also started to move into suburbs like Cerritos, Fullerton, Glendale and Irvine. However, many working class immigrants and elders stayed in the Koreatown area.

Though many Korean immigrants moved out, Koreatown continued to develop into a hub of commercial activities with the flow of investment from South Korea. There are numerous night clubs, shopping malls, cosmetic stores, restaurants, PC rooms, karaokes, and spas in the neighborhood. The construction of bars and clubs attract many people who desire the lively nightlife. While these night time establishments allow many Koreans to get the feel of a mini- Seoul, these after-hour spots inevitably produce serious social problems such as gang violence, drunk driving, prostitution, and other crimes.

Very recently, many wealthier Korean immigrants who left Los Angeles Koreatown are returning with the construction of high-end condominiums and apartments. These returning residents include those who sent their children to college, young couples, and college students seeking the urban life style. As a result of the newly-built residential places, rent prices in Koreatown are skyrocketing and many low-income residents are being evicted from their homes.

With the growing number of transnational businesses and commercial buildings, Los Angeles Koreatown is projected to grow further. However, rising rent costs and other urban developments in Koreatown negatively impact on low-income families who live, work, and raise their children in the community.

References

1. Abelmann, Nancy, and Lie, John (1995). Blue Dreams: Korean Americans and the Los Angeles Riots. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

2. Chang, Edward T., and Diaz-Veizades, Jeannette (1999). Ethnic Peace in the American City: Building Community in Los Angeles and Beyond. NY: New York University Press.

3. Choy, Bong-Youn (1979). Koreans in America. Chicago: Nelson-Hall. 4. Chung, Angie Y. (2007). Legacies of Struggles: Conflict and Cooperation in Korean

American Politics. Stanford: Stanford University Press. 5. Chung, Angie Y. (2000). “The Impact of Neighborhood Structures on Korean American

Youth in Koreatown.” Korean and Korean-American Studies Bulletin, 11(2): 28-53. 6. Min, Pyong Gap (1996). Caught in the Middle: Korean Communities in New York and

Los Angeles. Berkeley: University of California Press. 7. Teraguchi, Daniel Hiroyuki (2006). “Generative Thinking: Using a Funding Proposal to

Inspire Critical Thinking.” In Edith Wen-Chu Chen and Glenn Omatsu (Eds.), Teaching about Asian Pacific Americans. Lanham, MD: Roman and Littlefield.

Click on READ MORE for Korean translation

© 미주

한인 역사

번역: 이찬행 (뉴욕주립대학교)

로스앤젤레스

한국교육원 2009

제7장 로스앤젤레스 코리아타운: 과거와 현재

배경:

현재 윌셔 지구에 위치하고 있는 로스앤젤레스 코리아타운은 한인 인구 및 한인 소유 비지니스의 급증에 따라 1980년 로스앤젤레스 시정부로부터 “코리아타운”이라는 공식 명칭을 얻었다. 앤지 정에 따르면 윌셔 지구는 1950년대 이전까지는 백인들의 거주 및 상업 지역으로 기능했다. 그러나 1948년 주거 분리법이 위헌으로 판결되면서 사우스 센트럴 로스앤젤레스 지역에 살고 있던 아프리칸 아메리칸들이 이 지역으로 이동하기 시작했다.

최근 이민을 온 한인들의 상당수도 이 지역으로 모여들었고 이들은 현재 코리아타운이라고 불리는 지역에 비지니스를 오픈하기 시작했다. 1971년에는 3122 웨스트 올림픽 블러버드에 한인 최초의 미니 몰이 세워졌다. 서독 파견 광부로 일한 바 있던 이희덕은 이 건물에 올림픽 마켓을 오픈하였고 나머지 사무실 공간을 세입자들에게 임대하였다. 1971년 이후 코리아타운은 많은 변화를 겪었다. 한글 간판이 눈에 많이 띄는 올림픽 블러버드는 한인 비지니스 활동의 핵심이 되었다. 훗날 코리아타운은 점차 확장되어 웨스턴 애비뉴, 버몬 애비뉴, 다운타운 서쪽의 몇몇 주요 도로를 포함하게 되었다.

코리아타운의 과거

최봉윤에 따르면 1905년과 1907년 사이 약 1천여 명의 한인들이 보다 좋은 경제적 기회를 찾기 위해 하와이를 벗어나 미국 본토로 향했다. 로스앤젤레스에서 한인들은 1906년에 최초의 한인장로교회를 세우기 위해 벙커 힐 지역에 있던 주택을 렌트하였다. 낸시 아벨만과 존 리의 연구에 의하면 1910년대에 대략 40-50명의 한인들이 메이시, 알라메다 스트리트 그리고 벙커 힐 지역에 모여 살았다. 1930년대 무렵 한인들의 주거 지역은 버몬, 웨스턴, 아담스, 슬로슨 애비뉴를 포함하는 지역으로 옮겨 갔으며 한인장로교회는 1374 웨스트 제퍼슨 블러버드에 교회 건물을 세우기도 했다.

1965년 이민 개혁 이후 코리아타운은 한인 이민자들에게 주요 예정지가 되었다. 코리아타운은 급속히 성장했으며 새로 온 이민자들을 돕기 위한 사회 서비스 단체들과 미디어 기관들이 발전하기 시작했다. 코리아타운은 언어 장벽에 직면한 한인 이민자들에게 문화적 안식처를 제공했다. 오랜 기간에 걸쳐 한인들은 자신들의 사업 기술과 재원을 동원하여 코리아타운을 경제적으로 번창하는 커뮤니티로 탈바꿈시켰다. 1982년에는 코리아타운개발협회(KDA)의 협력으로 캘리포니아 교통국이 놀만디와 웨스턴 애비뉴 입구 사이에 있는 10번 프리웨이에 “코리아타운”이라는 표지를 내걸었다.

시간:

The Wiltern Theatre on the corner of Wilshire Boulevard and Western Avenue in Los Angeles, cir. 1938 (Photo from the Special Collections of University of Southern California)

Korean Presbyterian Church in Los Angeles, cir. 1930 (Photo from the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection)

코리아타운의 현재

아직까지도 코리아타운은 갓 이민을 온 수많은 한인들에게 마치 고향과도 같은 기능을 하고 있다. 하지만 이름과는 반대로 코리아타운은 다인종 지역이다. 이 지역 거주 주민의 최대 다수는 라티노이다. 1990년 인구 조사에 의하면 한인들은 전체 주민의 15퍼센트 미만을 차지하는 것으로 나타났다.

The Wiltern Theatre on the Earth Day, April 22, 2008 (Photograph by Chanhaeng Lee)

코리아타운은 아직까지 다양한 한인 커뮤니티 조직체들, 텔레비전, 라디오, 뉴스 미디어, 종교 단체들의 심장부와 같은 역할을 하고 있지만 소수민족들이 몰려 사는 고립된 공간이 갖는 특징, 즉 최근 이민을 온 사람들이 낮은 소득과 인종 차별 때문에 형성하게 되는 사회적 공간적으로 제한된 장소가 갖는 특징은 점차 사라지고 있다. 또한 주택 차별이 사라지자 부유한 한인들은 세리토스, 플러튼, 글렌데일, 어바인과 같은 교외 지역으로 이주하기 시작했다. 그렇지만 한인 이민 노동자 계급과 연장자들은 코리아타운 지역에 계속 남아 있다.

비록 많은 수의 한인 이민자들이 타 지역으로 떠났지만 코리아타운은 한국으로부터 투자가 유입되면서 상업 활동의 중심지로 발전하고 있다. 코리아타운에는 나이트 클럽, 쇼핑 몰, 화장품 가게, 레스토랑, PC방, 가라오케, 스파 등이 즐비하게 늘어서 있다. 술집과 클럽이 세워지면서 생생한 밤 문화를 즐기려는 사람들이 모여 들고 있다. 이러한 유흥 시설들은 한인들에게 마치 서울의 축소판에 와 있는 듯한 느낌을 주지만 동시에 밤 늦은 시간대의 영업은 불가피하게 갱 폭력, 음주 운전, 매춘, 범죄와 같은 심각한 사회 문제들을 낳고 있다.

최근 콘도미니엄과 아파트 같은 고층 주거 건물들이 세워지면서 타 지역으로 떠났던 부유한 한인들이 로스앤젤레스 코리아타운으로 돌아오고 있다. 이들 가운데는 자녀들을 대학에 보낸 사람들도 있고 도시 문화를 선호하는 젊은이들과 학생들도 있다. 새롭게 건설된 주거 공간들로 말미암아 코리아타운의 렌트비는 크게 올랐으며 그 결과 많은 수의 저소득층 주민들이 자신들이 살던 집으로부터 내몰리고 있는 형편이다.

트랜스내셔널한 비지니스와 상업용 건물들이 증가하면서 로스앤젤레스 코리아타운은 더욱 번창하고 있다. 하지만 코리아타운의 렌트비 상승과 도시 개발은 이 지역에서 일하고 살면서 아이들을 키우는 저소득층 가족들에게 부정적인 영향을 미치고 있다.

1. Abelmann, Nancy, and Lie, John (1995). Blue Dreams: Korean Americans and the Los Angeles Riots. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

2. Chang, Edward T., and Diaz-Veizades, Jeannette (1999). Ethnic Peace in the American City: Building Community in Los Angeles and Beyond. NY: New York University Press.

3. Choy, Bong-Youn (1979). Koreans in America. Chicago: Nelson-Hall. 4. Chung, Angie Y. (2007). Legacies of Struggles: Conflict and Cooperation in Korean

American Politics. Stanford: Stanford University Press. 5. Chung, Angie Y. (2000). “The Impact of Neighborhood Structures on Korean American

Youth in Koreatown.” Korean and Korean-American Studies Bulletin, 11(2): 28-53. 6. Min, Pyong Gap (1996). Caught in the Middle: Korean Communities in New York and

Los Angeles. Berkeley: University of California Press. 7. Teraguchi, Daniel Hiroyuki (2006). “Generative Thinking: Using a Funding Proposal to

Inspire Critical Thinking.” In Edith Wen-Chu Chen and Glenn Omatsu (Eds.), Teaching about Asian Pacific Americans. Lanham, MD: Roman and Littlefield.

✎ From the ☾ moon that shines bright as a shooting star ☆

Comments

Post a Comment